Top 7 Mistakes Most React Developers Make

Table Of Contents

React is a great JavaScript library for creating user interfaces.

It brings an enormous number of advantages for both, customers and developers.

But like any tool, if it is not used properly, it creates more problems than it actually solves.

Today we will take a look at the 7 most common mistakes that most of React developers make.

Direct State Modification

Every developer who starts working with React is taught that the state should not be modified directly.

But what are the reasons for this? What happens if the state is directly changed?

Consider the following example:

import React, { Component, Fragment } from "react";

import { Button, Text } from "./styled";

class App extends Component {

state = {

count: 0,

};

handleMutableUpdate = () => {

this.state.count = this.state.count + 1;

};

handleImmutableUpdate = () => {

this.setState({

count: this.state.count + 1,

});

};

render() {

return (

<>

<button onClick={this.handleMutableUpdate}>Mutable update</button>

<button onClick={this.handleImmutableUpdate}>Immutable update</button>

<div>Count: {this.state.count}</div>

</>

);

}

}

export default App;Notice what happens when the "Mutable update" button is clicked once.

Nothing?!

Then click on the "Immutable update" button and notice how the count has changed to 2:

Obviously we got 2 because the state was updated twice: directly and via the setState method.

By setState the component is re-rendered, thus starting the process of reconciliation.

Reconciliation is the process of updating DOM (Document Object Model) with changes to the component based on the change of state.

You can think of render as a function that creates a tree of React elements.

When the state gets updated, it creates a different tree and React needs to figure out how to efficiently update DOM to match the latest tree.

The default created by the React for the above example:

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: [

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: "Mutable update",

onClick: Function,

},

ref: null,

type: "button",

},

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: "Immutable update",

onClick: Function,

},

ref: null,

type: "button",

},

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: [

"Count: ",

0,

],

},

ref: null,

type: "div",

},

],

},

ref: null,

type: Symbol(react.fragment),

}This is what the new tree looks like after clicking on the "Immutable update" button (it remained the same except for the element with a type of "div"):

// The structure is the same, just this child element slightly changed

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: [

"Count: ",

1,

],

},

ref: null,

type: "div",

},The problem to solve: transform one tree into another most efficiently.

There are some generic algorithms that solve the given problem, but they all have an O(N3) complexity that makes them inefficient.

Imagine having to make 1 million comparisons to display 1000 elements.

Far too expensive to be used in real projects.

For this reason, React implements a heuristic algorithm with O(N) complexity based on the two assumptions.

Assumption #1: two elements of different types will produce different trees

For example, if the root elements have different types, React will tear down the old tree and build a new one from scratch:

<div>

<MyComponent />

<div>

<span>

<MyComponent />

<span>

<MyParent>

<MyComponent />

</MyParent>The old MyComponent will be unmounted and a new one will be mounted, although nothing has changed.

If there were any othe child components, they too would all also be destroyed and re-mounted.

If the DOM elements are of the same type, React goes through their attributes and updates only the changed ones:

<div className="parent" />

<div className="child" />React knows to only modify className.

If the component elements have the same type, the instance remains the same to maintain the state across renderings.

React updates the props of the underlying component instance to match the new element and calls the update lifecycle hook on it.

Then, the render method is called and the diff algorithm recurses.

When recursing on children of a DOM node, React iterates over both child lists al the same time and creates a mutation if a difference is found.

For example, adding an element to the end of the list is efficient:

<ul>

<li>One</li>

<li>Two</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>One</li>

<li>Two</li>

<li>Three</li>

</ul>React will match the first two elements and insert the third one.

But adding an element at the beginning or in the middle has a worse performance:

<ul>

<li>One</li>

<li>Two</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>Three</li>

<li>One</li>

<li>Two</li>

</ul>React will mutate each li element instead of realizing that two can be retained.

The solution to this problem is the subject of the next point.

Assumption #2: the developer can use a "key" prop to indicate which child elements might be stable across different renders

React supports key attribute, which is used by the library to match children in the original tree with children in the subsequent tree:

<ul>

<li key="one">One</li>

<li key="two">Two</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li key="three">Three</li>

<li key="one">One</li>

<li key="two">Two</li>

</ul>Now React knows that the elements with the keys "one" and "two" have just changed their position and the element with the key "three" is the new one.

After a general overview of how React performs updates, you might have guessed that a direct change of state would not trigger the entire reconciliation process and therefore the component could not be re-rendered.

Not Using "Key" Properly

After you have found out what the key is used for, it is necessary to know how to set it correctly, because if you do not do that, it will lead to unexpected errors.

Rule #1: "key" should be unique among siblings

In other words, every element within an array should have a unique key, but it should not be globally unique:

<ul>

{data.map((item) => (

<li key={item.id}>

{item.name}

{item.children.map((child) => (

<div key={child.id}>{child.name}</div>

))}

</li>

))}

</ul>child.id can be the same as item.id because they are not siblings.

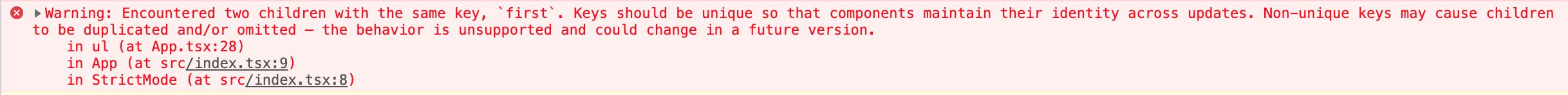

Wondering what happens when React encounters two elements with the same key?

The following warning is displayed in the console:

Rule #2: Use "index" as a "key" only if the list is static (it is not possible to reorder/add/remove elements)

Using index as a key will cause unexpected errors if the order of your list elements can be changed:

React does not understand which element has been added/removed/reordered since an index is given on each render based on the order of the items in the array.

Consider the following example:

const initialData = [

{

id: 1,

name: "First item",

},

{

id: 2,

name: "Second item",

},

];

const List = () => {

const [data, setData] = useState(initialData);

const handleRemove = (id) => {

const newData = data.filter((item) => item.id !== id);

setData(newData);

};

return (

<ul>

{data.map((item, index) => (

<li key={index}>

<input type="text" defaultValue={item.name} />

<button

onClick={() => {

handleRemove(item.id);

}}

>

Remove

</button>

</li>

))}

</ul>

);

};This list is rendered based on an index.

Let's try to remove the first value:

And it did not get removed!

Actually, it did but after we removed the first item, the second one got the key 0, and React thinks we removed the item with the key 1 because it is no longer on the list.

Changing from <li key={index}> to <li key={item.id}> solves an issue:

Be very careful with this, as this type of issue is extremely hard to debug.

Not Batching Updates

If you know React well, you might not agree with the above statement and you would be right.

In fact, React batches updates.

But not all of them.

Consider the following example:

import React, { useState } from "react";

const App = () => {

const [name, setName] = useState("");

const [surname, setSurname] = useState("");

const [age, setAge] = useState(0);

const handleClick = () => {

// These updates are batched

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

};

return (

<>

<button onClick={handleClick}>Fetch user</button>

<div>Name: {name}</div>

<div>Surname: {surname}</div>

<div>Age: {age}</div>

</>

);

};

export default App;Even though the state is modified three times, the updates are batched and the component re-renders only once.

However, if the state is updated within the asynchronous callback, these updates are not batched:

// These updates are NOT batched

// The component re-renders three times!

const handleClick = () => {

setTimeout(() => {

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

}, 1000);

};

...

const handleClick = () => {

fetchUser.then(() => {

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

});

};

...

// Even this causes multiple re-renders

const handleClick = async () => {

await fetchUser();

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

};This is the concept that many developers are unaware of, resulting in unnecessary updates and poorer performance.

No worries, there are at least two ways to solve this problem.

Way #1: unify the state

It is possible to replace the state variables: name, surname and age with a single object: user which contains all these properties:

// Unified state

const [user, setUser] = useState({

name: "",

surname: "",

age: 0,

});

// Event handler

const handleClick = () => {

setUser({

name: "John",

surname: "Doe",

age: 18,

});

};Way #2: wrap updates in unstable_batchedUpdates callback

The name of the method is a bit concerning but it is safe to use in production.

When using this callback, note that it should be imported from the react-dom package for the web:

import { unstable_batchedUpdates } from "react-dom";

...

const handleClick = () => {

setTimeout(() => {

unstable_batchedUpdates(() => {

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

});

}, 1000);

};

...

const handleClick = () => {

fetchUser.then(() => {

unstable_batchedUpdates(() => {

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

});

});

};

...

const handleClick = async () => {

await fetchUser();

unstable_batchedUpdates(() => {

setName("John");

setSurname("Doe");

setAge(18);

});

};Misunderstanding Deep And Shallow Copies

Shallow copy is a bit-wise copy of an object.

A new object is created that has an exact copy of the values in the original object.

If any of the fields of the object are references to other objects, just the reference addresses are copied i.e., only the memory address is copied:

const user = {

name: "John",

surname: "Doe",

other: {

age: 18,

},

};

const newUser = {

...user,

};

newUser.other.age = 22;

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 22}

console.log(user);

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 22}

console.log(newUser);Modifying other object updates the original value, as the spread operator does only shallow copy.

To update the nested property, each level of the nested data should be copied:

const user = {

name: "John",

surname: "Doe",

other: {

age: 18,

},

};

const newUser = {

...user,

other: {

...user.other,

age: 22,

},

};

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 18}

console.log(user);

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 22}

console.log(newUser);Deep copy is the copy that is fully disconnected from the original variable:

import cloneDeep from "lodash/cloneDeep";

const user = {

name: "John",

surname: "Doe",

other: {

age: 18,

},

};

const newUser = cloneDeep(user);

newUser.other.age = 22;

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 18}

console.log(user);

// Prints {name: "John", surname: "Doe", age: 22}

console.log(newUser);We can safely modify the other object, since it is now not connected to the user object.

The best way to make a deep copy is to use an external library, such as lodash.

Calling Functions Instead Of Passing As A Reference

Make sure that you do not call the function when you pass it to the component.

The following example contains invalid code because handleClick function is called instead of being passed by reference:

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick()}>Click Me</button>

}Pass the function itself instead:

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick}>Click Me</button>

}This problem is often seen in code written by inexperienced developers, but it is not that uncommon.

Forgetting To Bind Function Declaration

JavaScript uses the bind method is used to create a new function with given this context:

const user = {

name: "John",

surname: "Doe",

};

function getFullName() {

return this.name + " " + this.surname;

};

const boundFunction = getFullName.bind(user); // "bind" returns bound function

boundFunction(); // Prints "John Doe"Consider the following example of the React component:

import React, { Component } from "react";

class Welcome extends Component {

handleClick() {

console.log(this.props.greeting);

}

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick}>Greet me</button>;

}

}

export default Welcome;What would happen after clicking the button?

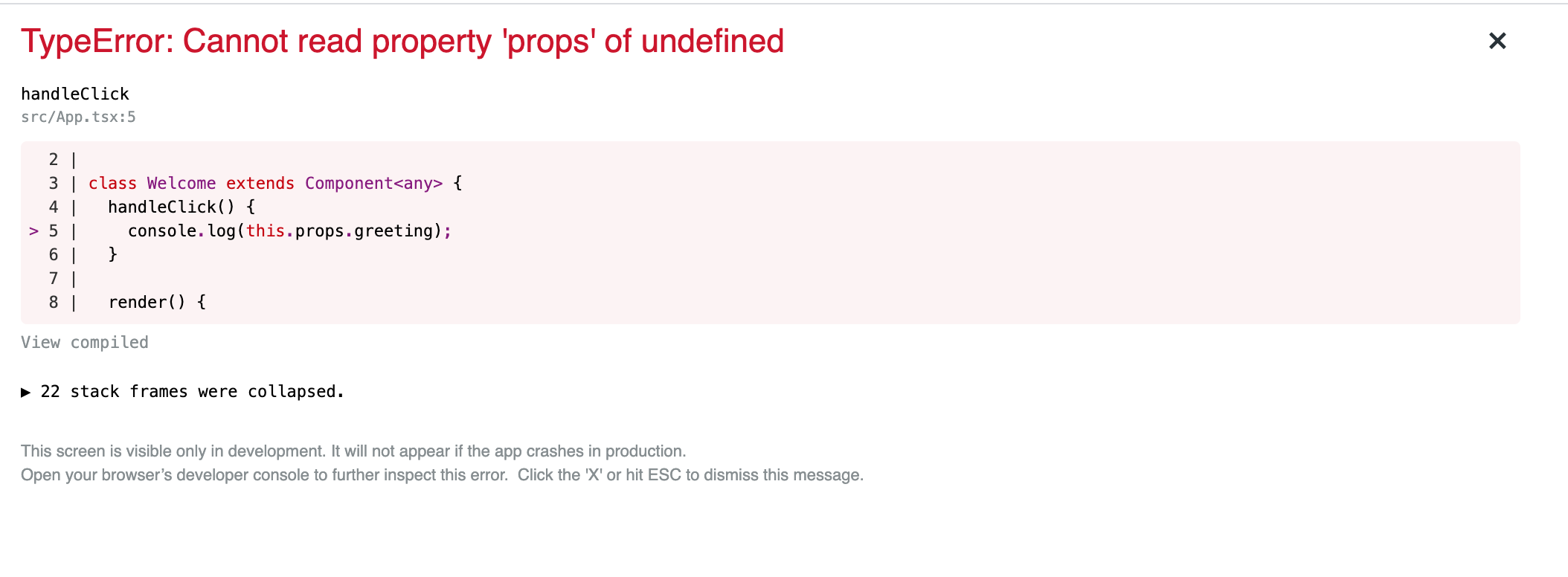

The following error will be thrown:

The reason is obvious: this is undefined.

But why? In the render function, this refers to the current instance of the React component, the component contains the handleClick function, so everything seems to be fine.

But it is not that simple. Behind the scenes, React assigns this.handleClick to another variable:

const onClick = this.handleClick;

// We lose "this" context

onClick();If we call the onClick function in the above example, the context of this is lost.

The context is determined at the time the function is called, not at the time of its definition.

Solution #1

One possible solution to this problem is to bind the handleClick function in the constructor:

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this);

}Solution #2

The second way of handling is to use arrow functions instead of function declarations:

handleClick = () => {

console.log(this.props.greeting);

}Arrow functions do not create their own this binding, they inherit it from the parent scope.

To learn more about the context of this refer to this article.

Solution #3 and #4

The handleClick method can also be bound within the render as well:

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick.bind(this)}>Greet me</button>;

}Or use arrow function callback:

render() {

return <button onClick={() => this.handleClick()}>Greet me</button>;

}These are also possible but not recommended solutions.

In the next chapter let's find out why.

Creating New Functions On Every Render

To bind a function to the context means to create a new one.

If the function is bound in the constructor, then only one function is created.

If the function is bound in the render, then a new function is created each time the render is executed.

In case of 1000 renders you will end up creating 1000 unnecessary functions.

The same rules apply to arrow function callbacks, they create a new function on every render and therefore lead to worse performance.

In summary, this approach should be avoided:

// Do not do that!

render() {

return <button onClick={() => this.handleClick()}>Greet me</button>;

}

...

render() {

return <button onClick={this.handleClick.bind(this)}>Greet me</button>;

}Summary

One of the most important steps to becoming a good React developer is to learn not only how things should be done, but also how should not.

In this article we reviewed 7 common mistakes that most developers make and how to avoid them.

Do you know of any other anti-patterns?

Share them in the comments below.